Tariq ibn Ziyad: The Horseshoe at Gibraltar and the Fall of the Last King of the Visigoths.

- Paravoz.es

- Nov 29, 2025

- 4 min read

Updated: Nov 30, 2025

Gibraltar: More Than Just a Rock, It's an Emblem of an Era

Once, at the beginning of the eighth century, there was no fortress, no British police officers in berets, and no ubiquitous macaques stealing tourists' bags. There was only a rock—massive, rising 426 meters above the sea—and a Berber warlord with his army disembarking at its base. Today we call this place Gibraltar, but every time this word is uttered, it is an echo of the Arabic Jabal Ṭāriq, "Tariq's Mountain." This is precisely how history happens, without excessive rhetoric: one man leaves his name etched in stone, and that stone becomes the gateway to a new era.

Gibraltar today is six and a half square kilometers of pure theater of the absurd: a British enclave pinned to the southern coast of Spain. Here you find sterling pounds, red phone booths, and souvenir shops marked "The Rock." But for the historian, it is not just an enclave; it is the point from which not only Islam burst into Europe, but also the entire renewed cultural matrix of the Mediterranean: Arabic astronomy, Jewish philosophy, Roman law re-engineered by Muslim jurists. The Rock became a bridge.

Who Was Tariq ibn Ziyad: Berber, Arab, or Just a Myth?

The personality of Tariq ibn Ziyad is a phantom of history. We do not know where he was born (most likely in the foothills of the Rif, in the Nafza tribe). We do not know what he looked like (all "portraits" are the fantasies of 19th-century artists). We do not even know if "ibn Ziyad" was a patronymic or a nickname given for his conquests. We know only one thing: he was a mawla—not an Arab by blood, but a Berber convert who rose through the administration of the Umayyad Caliphate.

This is an important nuance. Tariq was not an Arab ashraf from the Quraysh lineage, but a self-made man. His master and patron, Musa ibn Nusayr, the Governor of Ifriqiya (North Africa), sent him on assignments but did not truly trust him. When Tariq asked for reinforcements, Musa sent him 5,000 men—but predominantly Berbers, considered second-class in the Caliphate's hierarchy. Arabs went into the elite infantry; Berbers went into the risky vanguard. It was, essentially, a high-risk expedition that could be written off in case of failure. But Tariq turned it into a triumph.

The Speech at Wadi Salṣa: Words That Became Blades

Before the Battle of Wadi Salṣa (July 711, modern Guadalete), Tariq is said to have burned his ships. This is a historical cliché repeated by Hernán Cortés in Mexico, and before him, by Alexander the Great at Gedrosia. But the Arab chroniclers, especially Ibn Abd al-Hakam (9th century), preserved his actual words. Not as poetic fiction, but as a military order:

Original (Arabic): «أيُّها الناس، أين المفرّ؟ البحر من ورائكم، والعدوّ أمامكم، وليس لكم والله إلا الصدق والصبر...»

"O people! Where can you retreat? The sea is behind you, and the enemy is ahead. I swear by Allah, you have nothing left but honesty and patience! You have left behind the homes of your fathers and children, and if you are saved, you will be saved together; if you perish, you will perish together. What can separate you from the sweetness of battle?"

This is not pathos. It is logistics. By cutting off all routes of retreat, Tariq created an army that could only advance. The Visigothic King Roderic, crushed by the disintegration of his own kingdom, stood no chance.

The Battle of Guadalete: Not 7,000 against 100,000, but Something Else

Figures in medieval chronicles are figures of speech. "12,000 Muslims against 100,000 Christians" is not statistics, but a symbol of imbalance. The reality was different. Archaeological data shows that Roderic's Visigothic army was likely 15,000–20,000 men. Modern historians (F. W. Hodges, R. Collins) tend to believe that Roderic's army was comparable in number but ideologically bled dry. The sons of the late King Witiza, rejected by the usurper Roderic, defected to Tariq's side. Part of the nobility simply failed to show up for the fight. The key was not numbers, but the split within the Visigothic elite.

Roderic himself, according to the Mozarabic Chronicle of 754, "perished in the heat of battle." The details of his death are unknown. Much later, in the 17th century, the Moroccan chronicler Ahmed al-Maqqari paints a dramatic picture:

"When Tariq saw Roderic on the throne under a silk canopy, he exclaimed: 'That is the king of the Christians!'—and cleaved his head with a sword."

But al-Maqqari wrote 900 years later, relying on oral tradition. Archaeological data from the battlefield near the Guadalete river shows the engagement was fast, chaotic, with no signs of prolonged defense.

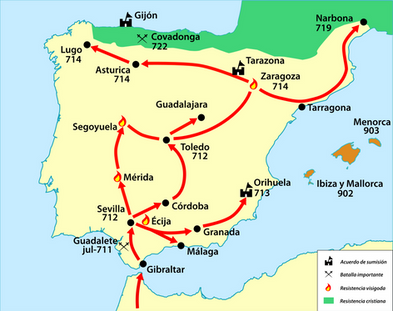

After Guadalete, there was no large-scale resistance. The Visigothic administrative machine simply ceased to function. Cities, populated mainly by Ibero-Romans, opened their gates: for them, the Visigoths were as foreign as the Berbers, but the latter promised fewer taxes. Within three years, control extended to the Pyrenees—not so much by the force of arms, but by the power of a vacuum.

What Became of Tariq: An End That Is Not Written

After the victory, Tariq was summoned to Damascus. Caliph Walid I, angered by the insubordination of Musa and Tariq, stripped them of their posts. Musa died in poverty. The sources are silent about Tariq. Perhaps he returned to Morocco. He likely died in oblivion. The main point is that he vanished, just as heroes vanish when their role is played out.

The Legend of the Horseshoe: The Truth We Choose

On the Rock of Gibraltar, there is a mark resembling a horseshoe. Legend says Tariq ordered his horse's shoe to be nailed into the stone to show: "we are here forever." The horseshoe remained.

The reality: the horseshoe was carved in the 18th century, likely by British engineers. Today, Gibraltar is a tax haven, a military base, a territorial dispute. But above all—a brand. Tariq’s name on British souvenirs sounds like an exotic touch. For Spaniards, the rock is a reminder of lost territory. For Moroccans, Tariq is a national hero (there is a monument to him in Tangier). For tourists, it's an Instagram photo op.

Tariq ibn Ziyad disappeared from history, but his name remained fixed in a toponym that outlasted three empires.